Brandon:

The man with the giant head is Leone Sinigaglia,

a Jewish Italian who, at 75, died as the Nazis arrested him for

deportation to a slave labor camp. His picture does seem grim, but

almost too solemn for the occasion of the portrait. I'm not even sure I identify with his music but when I listened, it evoked something in me...something indescribable and entirely vague. Who can tell what

he was thinking at this moment? I think, however, that his dome only

because of the length of his face, itself being more narrow and

elongated than the average human. I can't even say he's tangential to

our discussion as, other interest of full disclosure, I had to look him

up on Wikipedia, the source of most of my current knowledge on my

Italian and Jewish heritage.

As for Missoula, perhaps

it was just serendipitous, an occasion for two histories to cross in a

most unlikely way. I'd like to think that it was preordained, that

yours and your grandfather's lives needed to meet there. Is it possible

that this intersection hastened you more fervently to Japan? Was there

ever fervor? I realize that your preference for lack of reason to open

opportunity is exactly what I'm attempting to reason out.

I'm

curious about the other story you mention about Ridgefield; however,

regarding the one you told, it is amazing how kids behave. Clearly, the

child who belittled you knew nothing of which he was speaking, yet

something within his own self urged him to act so malevolently. As

children, we're so impressionable, which, of course, is nothing new.

Now, a father myself, I keep a minute-to-minute monitor on the language

I use because I don't want her to ostracize people unlike her, whether

they're Japaguese or Portapanese, or even chasing a penny down on the

school's gym floor. I may have mentioned that in the past, when I was

ridiculed in middle school for acting like a Jew, when I swiped a penny

up from the ground. I feel somewhat indifferent to that now, similarly

to your feelings about your bus incident. But, I never forgot that

either.

As for self-hatred and its transference into

love of a history I don't fully know, we so often love what we hate and

vice versa. I can't say I love being either Italian or Jewish...I don't

fully identify with either and always identify with one or the other

when it's convenient. I became intrigued when my grandmother told me of

relatives we lost to the Holocaust in Romania, especially because, at

the time, I felt that it validated my Jewishness. There was nothing

else to prove. But, of course, it validated nothing more than that one

day my great-grandmother stopped receiving letters from her

half-brother's wife, most likely because she was forced onto a death

train.

I can't say I inherited a mission to write but

it -and the approaching birth of my first daughter- inspired me. How

was I going to explain our heritage to my children knowing full well

that I didn't (and still don't) understand it myself. It's not

something I agonize over but it is something that I need them to know.

My two daughters are only a quarter Jewish, a quarter Italian, and then

it's anybody's guess after that. Just throw a dart at a map of Europe

and it'll likely land on one of their nationalities. Sometimes, I think

I identify more with being Jewish than anything else because of our

dwindling numbers, now only thirteen million, and it saddens me that my

daughters would have been considered non-Jews, according to the

Nuremberg Laws. The Jew would have been sufficiently bred out. Should I

be heartened to know that they're more Italian than any other

nationality in their blood?

This brings me to the one

question I have for you, Brandon. In THE GIRL WITHOUT ARMS, you write

about how you want children, when formerly you did not. In wanting

children, do you wonder how you will explain to them the histories that

comprise their beings? Will you explain it to them?

I

apologize if I've not answered all of your questions...there's simply

too much to try to answer. And, I haven't proofread this, so forgive

any inconsistencies.

Your friend, always,

Adam

Adam,

There's

a photograph further up in this conversation of a man with an enormous

(hydrocephalic?) head. Who is he? Did you mention him already? His head

is terrifying. I cannot help but think that his enormous head is

concealing something truly monstrous, something struggling to break free

from the confines of the man's enormous skull, a secret (or maybe a

sick joke) that if released would become an unstoppable contagion, you

know what I mean? And the look in his eyes: the look of pure,

calculating death. I hope you don't take offense to this -- I mean, if

this man is one of your ancestors. If so, and in exchange, I've posted a

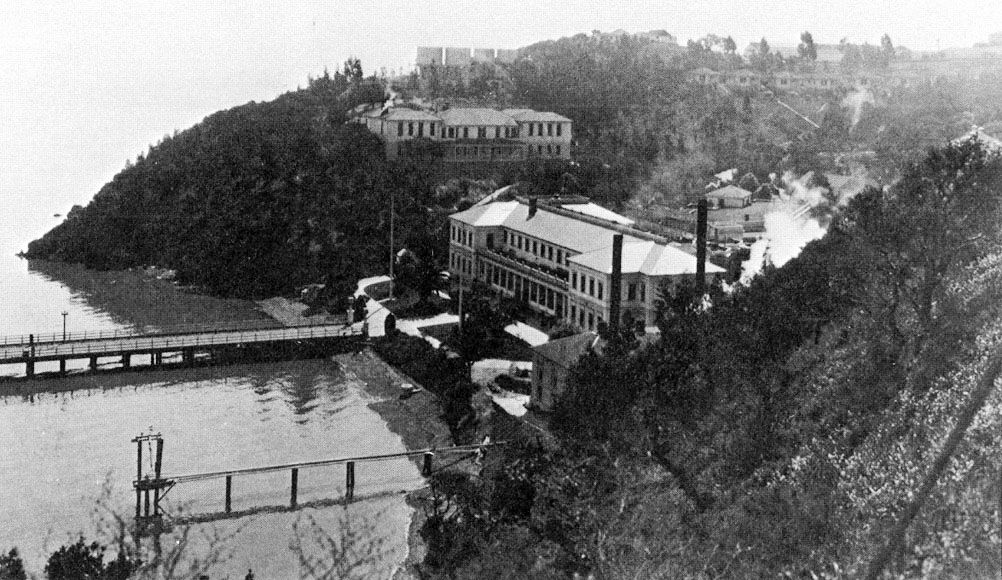

photo of my grandfather (above). This was taken at Fort Missoula's

Department of Justice camp, in 1943. He's getting fitted for a wig in

preparation for a performance. To answer Liz's question as to whether or

not it was coincidental that I chose Missoula as a home for four years,

knowing that my grandfather had been incarcerated there: I don't know.

Yes and No. I've been asked this question a lot, and especially since

I've written so much about his imprisonment, and I'm still not sure,

though I suppose I cannot deny at least the subconscious understanding

that I had to be there, to live in that environment, in order to know,

if only fractionally more, my grandfather and his experience, and

especially if I had any illusions of writing about him. I think I only

realized why I was there after the fact, though I'm still trying to

understand why I've lived anywhere. For example, I just moved to Tucson,

Arizona three weeks ago, and I have no concrete reason why. Which I

prefer, actually. The gap in pure reason allows for much greater

possibility.

Two quick things, because I can't even begin a gloss on

my time in Japan. Ostracism: I was never ostracized, but I was called

out once for, as I say, not being white, I guess: on the school bus,

first day of first grade, Scotland Elementary School, one of the older

kids started making fun of me for being "Portuguese." He pulled at the

corners of his eyes with his fingers, you know, in that typically

offensive manner of depicting Asian eyes, and in a high-pitched voice,

yelled at me, "Portuguese, Portuguese!" Of course, he had no idea what

he was talking about, but I was offended, and since "Portuguese" sounded

close enough to "Japanese" (the "-ese"), I felt like he KNEW something

about me that I didn't yet know. I blushed, and was quiet. I haven't

forgotten that. That was the extent of being picked on for NOT being

white, though not necessarily for being something else, since the dude

misfired. I have another Ridgefield, CT story related to this, but I'll

save that shit for later ...

Anyway,

brother, there is so much to respond to, and especially in the field of

SELF-HATE, and in the proposition of it being an inherited trait passed

down through the ages of a particular ethnicity or community. Perhaps

we should spin off another page on this blog devoted exclusively to the

topic: a private confessional. I could find so much there by which to be

confused and angered and INSPIRED. Of course, what is most interesting

to me, right now, anyway, and in the context of this conversation, is

how that, and your, self-hatred, has engendered the urgent attempt to

"uncover and archive as much family history as possible" before your

ancestors have all finally broken with this earth, this incarnation.

What I find most interesting is the idea that HATRED, self- or

otherwise, could be transmuted into LOVE, and in the form of rescuing

the casualties of that self-hatred and preserving them in a way that not

only might put them beyond the reach of malevolence, but also return

them to life and to liberty!

This

might be rewinding things to the very beginning, but good: Why do you

think or feel that it is important to "uncover and archive as much

family history as possible"? I mean, you personally. At what point did

you realize that this was important? What do you fear in not being able

to achieve what you're envisioning -- that is, as family members

continue to pass away, and the individual histories go lost to the ages?

And how is this related to the investigation into your identity, as

taking place, partially, on this blog? Wherefore the fire inside you?

And lastly, how does this all relate to writing? Do you ever feel like

you've "inherited" a particular mission?

By

the way, I realize these responses are LONG, but they can only be long,

right? Until we blow up our fucking computers and move down the street

from one another. The problem, of course, is that so much falls through

the cracks in our responses -- so many questions left unanswered, so

many profound statements and stories left unaddressed. But such is the

flow. Missing you deeply,

Brandon

Brandon:

Welcome home from your travels, of which I'll ask momentarily.

In

answer to your first query: self-hate. It is the reason for the

nascent denial and subsequent attempts at "exorcism" of my Jewish

heritage and yet the most trite characteristic description of Jews. The

two may as well be synonymous. And, while I was terribly insecure as a

teen, what teen isn't? Surely, this is not an adequate reason for such

disgust. I'd hypothesize that after millennia of external, targeted

hatred bent on Jews for so many centuries, what else could this who are

Jewish feel toward themselves? If you hate a child long enough, if you

belittle and bully a juvenile from the moment of his or her existence,

won't that child believe it? Won't that child hate himself, too? Maybe

that's too easy. Nevertheless, I can't help thinking that there's

truth to the self-hatred that courses through American Jews. Perhaps

it's reaching. Perhaps, it simply exists because so many influential

Jews say it exists. Philip Roth, of course, the extreme example, harps

on it, feeds on it, brands it into his work. As much as I love and

embrace his novels, as much as I write under his pervasive influence, if

Philip Roth were your cultural leader, wouldn't you hate yourself, too.

I

don't recall the "moment" when I realized this, although there were

certainly defining events: one of our mutual friends attempted to

convert me to Catholicism, insisting that I pray each night in order to

avoid Hell; I was ridiculed for picking a penny up from the gym floor,

the money-hoarding Jew image clearly portrayed by this act; and, of

course, my fervent participation on those Christian weekend retreats in

order to get laid. Whether these events were formative or coincidental,

I could argue for both. Undoubtedly, though, the self-hatred persisted

sufficiently enough to place me, now, in the position of scrambling to

uncover and archive as much family history as possible before the last

of my elders leaves this existence. Within this, there is a defining

moment that has summoned back to my Jewish lineage: the discovery that

Romanian relatives were, in fact, victims of the Holocaust. There is

shame, of course, that it took such a realization to endear me to

Judaism but I suppose it's never too late.

As

for your second batch of questions, my parents and I never discussed

our ethnicity because I was never interested until much later in life.

Where this trip to Japan may be a defining moment for your

self-understanding, my visit to the National Holocaust Museum and every

viewing of Goodfellas are defining moments for me. There were

never real discussions about these things with my parents because we

wanted to blend into the Ridgefield pastoral; the was no room for yarmulkes or unibrows. My brother's bar mitzvah

may as well have been a confirmation ceremony as given the Gentile:Jew

ratio of 3:1. It's not that we actively discouraged discussion of the

topic. It's more that we became complacent about being Italian or

Jewish. This complacency, in my case, offered no resistance to my

rampage of assimilation, albeit a transmogrification into the fringe.

My

questions to you: what was it the majority saw in you when you write

that you were ostracized for being "something?" Was it that you were

Japanese or simply edgy and apart from the norm? More importantly, what

of your travels to Japan? I wonder if they have influenced your

self-understanding or if it is just my hope that this is the case or

even, perhaps, that I hope you want this to be true.

And,

a question from my wife: was it coincidental that you chose Missoula,

the city of your grandfather's incarceration, as your home for the

better part of the last decade?

Adam

Adam,

At

the risk of breaking the narrative, let me apologize for the lapse in

response. We're now in Kaohsiung City, in southern Taiwan, and much

movement has transpired since you last wrote. And yet, I've been

carrying this conversation with me, as it feels as important to absorb

it as it does to unfold it, or let it unfold. We are flying to Japan in

fifteen days, so an immediate relevance here, in thinking through some

of these things.

Before

confronting your battery of questions, one persists for me, and maybe

unanswerable -- and that is: What is (or was) the source of your

"self-directed anti-Semitism"? Where did this come from, and when did it

arrive? Do you recall a point, or moment, in your youth, when you

suddenly felt this specific animus, at least ambivalence, towards being

Jewish? Did it originate purely within a certain regard, or lack

thereof, you held for yourself? Or did it arise from some external

source? Was there some kind of personal or familial crisis out of which

these feelings arose? No doubt this is a supremely difficult question to

answer, and one likely at the root of this entire inquiry. Maybe we

could take for granted the grace of objective distance to the subject.

But, I'm curious -- and especially because you reference it as a fact,

having "wanted nothing to do with being Jewish," defying it with your

fleeting turn to Jesus, etc., without establishing the conditions that

made it so. A lot of hard-hitting questions up front, I know, and maybe

better addressed in the midst of some other thought, or walking in the

woods. But here we are ...

I'm

perpetually struggling through my own take on things, and part of that

struggle is in understanding -- to address one of your parting questions

-- whether or not I embrace/embraced both my Japanese and "English

Isle" selves equally. The answer is no, though perhaps I would also

qualify the word "embrace," since I do embrace all of my facets equally,

however I might be more interested in investigating the nature of one

facet over the others. My mother did not imbue my sister or me with a

foundational curiosity in the ethnic heritage/history of her side of the

family. She rarely referenced her Caucasian (Scottish, Irish, English,

Welsh, etc.) roots, and in fact, was much more invested in the culture

and history of far-eastern Asia than she was in her own culture and

history. She has traveled throughout Japan, China and Korea, speaks a

little of the language of each country, and for a time, was friends

primarily with Asians and Asian-Americans. She studied East Asian

religion and Japanese art history in college. Though she didn't reject her

own ethnic heritage, she certainly did not embody an active interest in

it. This has changed a little bit in the intervening decades, but so it

was true as we were growing up. What complicated this further was the

fact that my father -- himself Japanese-American, the second son of two

Japanese parents -- was NOT particularly invested in his own cultural

heritage, at least as far as I could perceive. The origins of his more

"passive" relationship to Japanese culture and history, for example, can

be traced back to his own parents' experience as "enemy aliens" during

World War II; they emerged from that experience determined towards a

more inconspicuous citizenship. So while my father is Japanese, my sister and I inherited our Japanese culture primarily from our mother,

who is Caucasian, and if we didn't exactly inherit our Caucasian

culture from our father, we at least inherited a complicated

relationship to cultural heritage, in general. So, some things to sort

out. In the past decade or so, my father has thrown himself fully into a

different relationship with Asia -- he runs a non-profit organization

based out of Laos, and travels frequently to southeast Asia and China.

So

... my interests began locally, and were also related to immediate

conflict. Let me put it this way, for a second: I was never picked on

for being white. I was however picked on for being ... something. These

encounters have been infrequent, since I believe I am more nebulous

than not, but ... I'll write about this later. Anyway, I have always

been acutely fascinated by the wartime internment of Japanese-Americans,

and have also always been acutely fascinated by the bombings of

Nagasaki and Hiroshima. My grandfather was born in Hiroshima, and he was

imprisoned in a federal detention center in Missoula, Montana, in 1942.

So my interest begins there, with the locality of my grandfather, and

the locatable experiences of his life. I know very little about my

mother's parents -- again, partly because of something that wasn't fully

transferred between her and me, and partly because that history is more

diffuse. Maybe it only feels that way. After all, my father's parents

are both 100% Japanese. Any investigation I might initiate has at least a

superficially concentrated source. My mother's parents, however, are

each a different combination of Caucasian ethnicities; in addition to

those of the British Isle, there is also a low percentage of each of

German and Italian on my grandmother's side. Any investigation I might

initiate through that side of my family must already begin in numerous

landscapes at once. Of course, it is monumentally worthy, and I will get

there. I'm being slightly reductive in everything I'm saying -- there

is boundless complexity on all sides, and especially in my parents'

respective relationships with their own backgrounds. But ... there must

be something else at the root of this, as well, above and beyond what I

just said.

While

the delineations are fresh on the mind, I'm curious now about your

parents, and about each of their relationships to their ethnic

heritages. What was imparted to you and your brother, what was withheld

-- what seemed absent from the conversation, and what maybe still is

absent? Were they vocal about their own feelings and questions about

their ethnic backgrounds? Wasn't your father excommunicated from the

Catholic Church for marrying your mother? I vaguely remember this,

though more as a headline than a multidimensional story. Have their

relationships to their own backgrounds changed as they've gotten older?

Do you talk with them about any of these things -- what we're talking

about now?

Brandon

Brandon,

Much

then as it is now, my "private" and "public" lives were entirely at

odds with each other. They chose not, or rather I refused, to let them

coexist. And, it was very much a result of my own self-directed

anti-Semitism. I had no knowledge of being Jewish or Italian, wanted

nothing to do with being Jewish, and further denied it's existence in my

DNA, if I may suggest that there is a genetic code for such. My

fleeting relationship with Jesus was in fact a denial and largely a

defiance. Simultaneously, it validated my Italian heritage and allowed

me to create a life of half-truth.

Perhaps

it might have been different had I had a similar experience to your

trip to Japan. Regardless, I was quite willing to accept the Italian

and shun the Jew. Had I the knowledge of my perished ancestors during

the Holocaust in Romania, I wonder if that would have affirmed to me

that I was a "certified" Jew. Would I have embraced it? I don't know.

I had the melodramatic and adolescent notion that history with the

Holocaust would have authenticated my Semitic roots. But, even my

"private" self was conflicted as I wanted the authenticity but refused

it with inaction: I chose not to be bar mitzvahed because, as I write in

Mischling, I didn’t want to learn that “froggish language.”

I

struggle to understand the need for this authentication and all I

conclude is the invisibility of my heritage; I didn't and don't appear

Jewish. Perhaps I look a little Italian but do not exhibit any of the

stereotypical Jewish traits. Being "American" or an Italian American or a

Jewish American was simply not enough to satisfy or interest or

engender investment in familial history.

When

finally I resolved that I could not understand it, I isolated it,

disguised it, neglected and forgot it. So, when you ask, "What did you

know, and not yet know?" I answer, "Nothing, and everything." I often

speak in hyperbole but any knowledge of my separate selves, anything

other than superficial facts, was limited to what I learned in movies

and books.

And

so, Brandon, I ask you is whether you isolated one of your "selves,"

consciously or unconsciously? Did your selves isolate you? If you

didn't segregate either side, then why not? Did you embrace both

Japanese and English Isle equally? Certainly, as I've written elsewhere,

I've rarely acknowledged all of my selves equitably. In asking, I feel

as if I've loaded the question. You seem to have had a much different

experience in relation to your ethnicity.

Adam

Adam,

There

are so many ways to think about this, and so many of them will prove

ineffectual against the wall of what is true: Who knows? There is no way

of going back to truly know, and yet in every sense, the past has

become the present.

I

think of a couple of things right away. One: that as teenagers we took a

great deal for granted. This is beyond dispute. And this includes,

among an enormous swell of other ideas, places, possibilities, et

cetera, each other, as friends, as individuals in the world. However

unfortunate this was then, I don't see it as necessarily a bad thing,

since we come into our curiosities and appreciations organically, when

we do. But even more so, part of this "taking for granted," when not due

to a lack of awareness, attention or respect, helped us be present, in a

way, with each other, without feeling the need to form totalizing

pictures of each other. We enjoyed hanging out, and that seemed to be

justification enough for who we were, why we were friends, etc. Deeper

inquiries into our identities would come later, once they were made

vulnerable and explicit by the world beyond childhood ...

Of

course, it feels like a cop-out to articulate it this way, because we

did talk a lot back then -- we spent a lot of time talking, discussing

things, figuring things out, as friends, as friends within a group of

friends. The specific question is why didn't we talk about our

ethnicity, our backgrounds? And I might ask in return: Didn't we? I

don't remember talking about this in a focused way (i.e. in the way that

we are starting to now), but I also don't remember NOT talking about it

at all. Certainly these things were on our minds. But, this brings me

to my second thought ...

And

that is that our identities are always divided, and in a primary sense

between our "public" and "private" selves. I know that my "private" self

of the 1990s spent a great deal of time thinking about my ethnic

heritage, and in relation to the cultural and social context of

Ridgefield, Connecticut. Admittedly, this thinking revolved around being

half-Japanese, more so than being of Scottish and Irish ancestry, since

there were so few people of Asian descent then living in Ridgefield. My

family visited Japan for the first time when I was 10 years old, and

that trip had an enormous impact on me, primarily in the form of opening

up a wealth of questions about my relationship to being Japanese, and

especially a new understanding of not being Japanese, but being Japanese-American,

and the differences there. My awareness of Japanese-American internment

during the second World War began intensifying around this time as

well, with my grandparents at the center of my concern. But all of these

engagements -- questions, considerations, researches, etc. -- were more

or less "privately" held. What I shared "publicly" was different. That

is to say, what I withheld, or (maybe) sublimated, or hadn't yet been

able to articulate to my "private" self, or just didn't feel confident

enough to express, was vast. And so, despite reveling in the fact that

my friends were so good at helping to talk/work through the problems and

questions of life, some things were left out of those conversations. Of

course, there is nothing extraordinary about the divided self, in this

explanation -- its how we live our lives! And often needfully so ... And

yet, its not so simple. There were certainly obstructions to talking

about these things, you and me, and whatever those obstructions might

have been, owe some debt to the "cultural and social context of

Ridgefield, Connecticut." It was an age, we were young, we were just

then coming into the world, but we did so in a very particular place.

So

I'm curious then about your "private" life back then, in the

early-to-mid 1990s. Are you able to differentiate your "private" life

from your "public"? Are you able to make sense of what you withheld from

one or the other, from one or the other? You were writing poems and

short stories, reading novels by Andre Schwarz-Bart (The Last of the Just)

and Philip Roth (right? or was he later?). Hell, you were even

investigating your relationship to Jesus H. Christ -- which didn't seem

so much an investigation as a reaction, in fact. But a reaction to what?

Do or did you feel like your "private" and "public" lives/selves were

at odds with one another? What was your relationship to your ethnic

heritage at the time? What did you know, or not yet know? That's a huge

question, I realize, but maybe to begin placing us individually --

beginning to understand who we were "privately" -- in order to better

understand who we were "publicly," and therefore why we did or did not

ever talk about things that were obviously so important to both of us

...

Brandon

Brandon:

Why, my good friend, do you suppose that after nearly twenty years of friendship, only now are we discussing each other's ethnicity? That only now are we beginning to ask about questions of heritage, if one might call it that? Was I do afraid to ask? Too concerned of offense? Too disinterested? Too complacent? Perhaps, there's no need for dialogue or even thought or attention to the topic. Perhaps, such over-thinking is uncomfortable, even melodramatic. Perhaps, I am over-thinking that we were ever uncomfortable about it.

A little exposition for the casual reader: Brandon is a Japanese and Scottish-English-Irish American, I am an Italian Jew. We've been friends since 1992: freshman year of high school in a quaint New England town known for many events in history, not for its diversity. In that time, we've recently determined that we've never discussed our ethnicity. Not once.

Shouldn't we have, if only once? I'd like to think that our friendship transcended such a necessity. I'd like to think that we never knew about such differences between us, that I never noticed the Asian features of your eyes, that you never heard me mention Yom Kippur. This, however, is hubris.

Why didn't we ever talk about this? Was it repulsion or disinterest? Even now, why am I writing with you on this in a forum where I may censor my language, revise my thoughts, and calculate my intentions without fear of the misinterpretation of dialogue?